How worried—or excited—should you be about artificial intelligence? Will it change how you work, make your job easier, or replace you altogether? A panel of faculty experts from UNC-Chapel Hill share observations, insights and advice for leaders who are contemplating how AI will shape the future of their organizations—and what this rapidly emerging technology may mean for how we work and live in the not-so-distant future.

“The future could be glorious or terrible.”

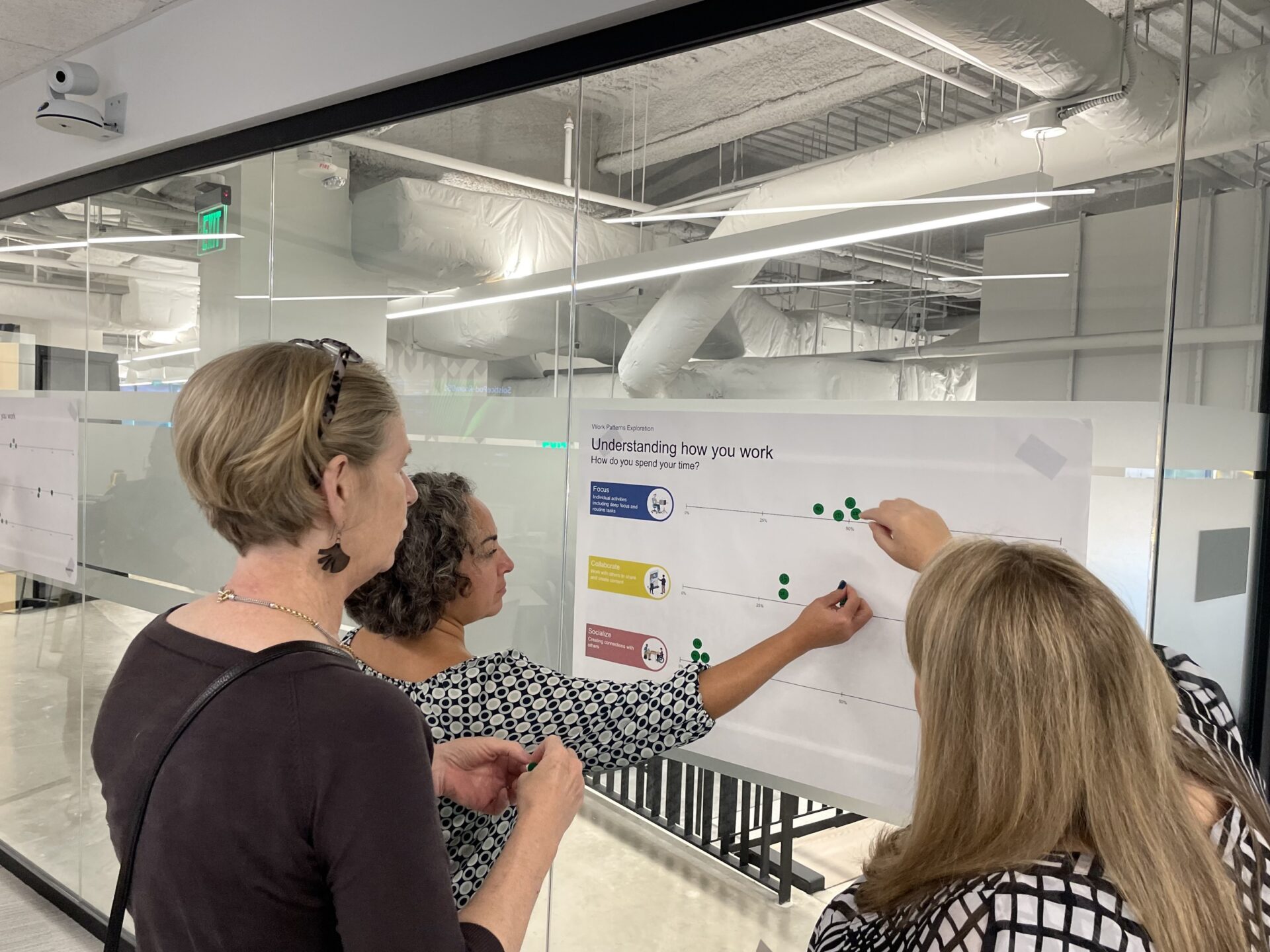

With these seven words, Thomas Hofweber, PhD, professor of philosophy at UNC-Chapel Hill, summed up the shared sentiment—a coinciding blend of enthusiasm and trepidation—of those who gathered at the Innovate Carolina Junction to probe the powerful potential of artificial intelligence (AI) to transform how people work. The group of industry technologists, small business owners, startup founders, faculty and students convened for a conversation titled “Beyond AI Anxiety: How to Thrive With the Intelligent Tech of Tomorrow.” The event is part of the Signature Series, which is hosted by Innovate Carolina—UNC-Chapel Hill’s central team for innovation, entrepreneurship and economic development—to explore pressing and practical issues like the future of work.

Hofweber joined fellow Carolina professors Mohammad Hossein Jarrahi, PhD, associate professor of information science and Mark McNeilly, professor of the practice at the Kenan-Flagler Business School, on a panel of AI experts to lead the lively conversation.

Here are seven core questions—and thoughtful answers from our AI experts—to get your mind turning with a mix of intrigue, optimism and caution about the AI-driven world of tomorrow.

McNeilly: There are two primary types of AI: traditional AI that we use every day and generative AI. Examples of traditional AI are Siri, Alexa or when you perform a Google search—things that people have used for a long time. That kind of AI exists behind the curtain, and you don’t really know you’re using it. Generative AI is different. One distinction is that generative AI creates content: text, video, audio, code and 3D models. The web is driven by content, so we live on it. Generative AI can also interact with us in a more human-like way, and it could also fully replace some of the tasks that we do, unlike behind-the-curtain AI.

Hofweber: Another contrast between generative AI and other AI models is that the other versions do what’s called regression or classification. For example, if you want to predict the stock market and ask, “What’s the value of this particular stock going to be?” that’s a regression problem. Or classification, where you want to see if an image belongs to one of 1,000 different categories. With classic AI, you’re answering questions like, “Is this an image of a cat or a dog?” You input an image into an AI model, and it will classify it and tell you with 90 percent confidence that it’s a cat. These uses of traditional AI contrast with generative AI, which instead produces content, like an image or text.

Hofweber: Modern AI is different from the development of the Internet or other past technologies because past technologies couldn’t overcome the limitations of human beings. As human beings, we are limited creatures. We are flawed. We have a certain limited range of intelligence and processing power. Today, AI is on the verge of overcoming human limitations, which could fundamentally change things for the positive and negative. In the future, if the limitations of human beings go away, there could be tremendous progress that wasn’t previously possible. Or things could really go downhill.

Jarrahi: Everything boils down to self-learning. The new AI systems are powered by deep neural networks and deep learning. These systems are different from the previous generations of AI or information systems like ERP, CRM or analytics that organizations have used for decades. The new AI systems develop their own learning and their own logic.

Hofweber: In old-style AI, you would program the whole system. You would write code and tell it what it’s supposed to do—like a list of instructions. This is not how contemporary AI works. With today’s AI, you write a code for the basic structure of the neural network that you want to train. And you write code for how to train the network. Then you give it data, run that code and, after a long time of training, you arrive at a trained neural network. But the technology itself that you use—the model—Is not explicitly coded, it’s trained. This is important for questions about transparency and our ability to explain and interpret what generative AI produces. If you want to know: Why did the model give me this particular answer? Why did it produce this particular image? Where did it get this information? You can’t easily look inside and explain why something happened, contrary to traditional AI that was explicitly coded.

McNeilly: I think certain industries like higher education, banking, consulting and others are more likely to be impacted than others. But I would focus less on industries and more on roles—specifically, customer-facing roles that exist in almost any organization: marketing, sales, and R&D to a certain extent. Those customer-facing functions are where you’re already seeing AI deployed because the technology does what people do. Perhaps the effect will be less in supply chain, finance and some other functions, but those roles will feel the impact of AI, too.

Jarrahi: AI isn’t going to put a lot of people out of jobs, but it will change us. If we learn from the bigger technological advancements of the past—the Internet, electricity or when people invented the wheel or fire—some people went out of business. People had to adapt; as a human race, we’re very adaptive. I tell my students that what makes them distinctive are their human-centered capabilities. Those are our competitive advantages. For instance, expertise is still very relevant. In a lot of cases, managers make intuitive, gut-feel decisions. Those decisions aren’t arbitrary. They come from years of internalizing tacit experiences with other people. Yes, machines can write a very nice letter with a specific connotation for a specific audience, but that’s only a low level of emotional or social intelligence. That doesn’t get to the level of back-and-forth engagement between two humans.

McNeilly: At least in some fields, AI may give less experienced employees an advantage. Research conducted by Boston Consulting Group with Wharton Business School, Harvard Business School and the MIT Sloane School of Management showed that when you equip people with ChatGPT, those who initially demonstrated lower performance on business tasks increased their performance much more compared to the most skilled employees. So, if you’re a senior consultant who built up 20 to 30 years of experience, your experience may no longer set you apart. So, AI becomes a great equalizer. Organizations may be able to hire inexperienced people, give them GPT and phase out more experienced employees because the productivity difference between the two groups is minimal.

McNeilly: In the short term, I’m very positive about the benefits. We’re in a bit of an AI hype cycle right now, and it’s going to take time for people to implement the technology. But you already have things like Microsoft Copilot, which integrates into your Microsoft environment. That type of application should boost productivity and creativity. There are a lot of opportunities for people—including our students and faculty—to use AI tools to improve our human flourishing.

Jarrahi: The self-learning capabilities are the biggest benefit of AI. When we use generative AI in my own area of research, it shows patterns that we haven’t seen before. I’m also focused on the concept of human-AI symbiosis: how people and AI can work together rather than compete with each other. Since 2017, I’ve been researching human-AI interaction and have specifically studied the concept of algorithmic management—how algorithms automate and augment managerial functions, how they can help managers and how they might replace some managerial tasks. In a lot of instances, the power that people think these technologies possess doesn’t pan out when you actually bring them into an organizational context. Humans still have to be involved.

Jarrahi: One concern is lack of transparency. It’s hard to tell how machines arrive at a certain understanding given the architecture of a neural network. Even the AI designer, in many cases, won’t be able to tell you how a certain input resulted in a particular output. For example, I work with pathologists who use AI for deep learning. Sometimes the machine gives you 95 percent accuracy for certain medical decision making, which is better than most human doctors, but then it can’t explain why. So, the lack of transparency and inability to explain outputs are the biggest minuses, particularly for high-stakes decisions.

Hofweber: Another problem is that there’s no agreement on values. There are so many unresolved questions about morality, but even if you could resolve them, how do you put values into an AI system? How do you get AI to stick to those values? You could create explicitly instructed guardrails, but you can’t guarantee that AI will obey the values. This like a famous problem with Asimov’s Laws of Robotics. Explicitly stating the rules that a system is supposed to obey gives rise to several problems. The system might misinterpret those rules. It might have false empirical information and then misapply the rules. So, defining and adhering to values is a concern.

Jarrahi: Hallucinations are also a challenge. ChatGPT is really smart in some areas and really dumb in others—dumb to the extent that it will churn out stupid, dangerous ideas. It’s a language model that acts like a salesman who tries to convince you rather than be completely data driven. There was a legal case where a lawyer prepared a court filing using AI, and ChatGPT cited fake precedents that the attorney presented in court. ChatGPT completely fabricated the cases because it tried to make the case stronger, but not based on data and truth. AI tools aren’t truth engines, so humans must remain in the loop.

McNeilly: Government regulations will look different in different places. In China, regulations will be strict because the government doesn’t want to lose control. In the United Kingdom, regulations will focus more on privacy. The U.S. will probably be less regulated because that’s how we roll. And Japan will be much less regulated because it’s population issues. Within the AI industry, OpenAI has dedicated significant resources to work on alignment and safety problems. On the other hand, while firms pour money into developing AI, companies like Google and Meta are reducing the size of their safety teams.

Jarrahi: I look at bottom-up practice to see what people actually do. Three or four decades ago, big institutions controlled access to the best and brightest technologies. Today, things have shifted to consumerization, which means individuals can access and use tools like ChatGPT, whether or not big organizations want them to. Reuters conducted a large-scale poll on ChatGPT usage among U.S. workers, and while nearly one-third said they regularly used ChatGPT, 25 percent of those surveyed said they didn’t know what their company’s position on using AI was—or that they didn’t care. Right now, people operate under a don’t-ask, don’t-tell AI policy because AI helps them. With more distributed workforces, people act more like free agents. They are more invisible, and managers don’t know as much about what employees are doing so blanket policies aren’t going to work. When organizations tried to block social media, people just used it on their phones. The companies didn’t have control, and the same goes with AI. People are experimenting with how AI helps their own individual work, and that’s the way to move forward. The same is true with our students. The horse has left the barn. We can’t know how students are using AI, and I’m happy with how they’re experimenting with it. AI is a tool students can use, and there’s no way to block them.

McNeilly: At Carolina, we formed the UNC Generative AI Committee, which all academic departments and professional schools became a part of. There were two results: one was education for faculty, students and staff about generative AI. The second was developing guidance and resources for students, faculty and staff on how to properly use generative AI for their work. The goal is to help them increase productivity, creativity and knowledge in the applications of teaching, learning, research and operations. Looking at universities broadly, we talked to a reporter at the Chronicle of Higher Education who said she only is aware of three universities—UNC-Chapel Hill, the University of Virginia and Drexel University—that have created university-wide policies around generative AI. Businesses are also slow to act. Up to 50 percent of businesses recognize the risks, but only about 20 percent of them actually have AI policies.

Jarrahi: My optimistic vision is that AI will free up time, automating some of the things we’ve been doing: information synthesis, finding sources, sifting through web pages and finding the common denominator. ChatGPT is fantastic at information synthesis, so if you’re a domain expert, it can free up a lot of your time. In an ideal world, you could direct your attention to more human-centered, high-value work. It’s elevating humans through automation.

McNeilly: There are also people who won’t be able to elevate themselves to work on other things. There will be winners and losers, just like with globalization. The whole history of technology is about unintended consequences. Kranzberg’s first law of technology says that “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.” In this case, some people will get whacked by AI, and others will make a lot of money from it. There are people who will adopt it, use it effectively and elevate themselves by focusing on certain human qualities that will still be important: domain expertise, taking initiative, knowing how organizations work and how to move them forward, being resilient and adaptable, and having charisma. If ChatGPT takes over more of the writing, our human value, like during ancient Greece or Rome, will be our oratory and rhetoric skills—our ability to speak and influence others.

Hofweber: It’s inevitable that machines will become more intelligent than we are in basically every way. ChatGPT has already achieved that in many regards. The concern is that if you have another system that is more intelligent than we are, that’s an existential threat to humanity. A classic example is the situation of the chimpanzees. Chimpanzees are physically stronger than we are but slightly less intelligent. And they are on the verge of extinction because of what humans are doing, even though we don’t have anything against chimpanzees. We don’t consider them a threat and don’t want to make them extinct. We’re just competing for resources, and our slightly advantaged intelligence makes it much easier for us to take those resources. So, chimpanzees get pushed to the brink of extinction. This is the concerning analogy: that AI systems will become more intelligent than we are, and we will defer decisions and agency to them. The day will come when we’ll lose more control, and eventually machines will allocate resources to themselves. It feels like a fork-in-the-road situation in that the future could be absolutely glorious or terrible. Nobody really knows where it will go.

Jarrahi: Everyone has bits and pieces of the future with themselves. We come from different backgrounds and disciplines. I don’t believe in singularity or technological determinism. Never in history has technology taken over. I’m more scared about humans than technology. The future won’t be out of our control. It’s a matter of how we bring all this together. Through interdisciplinary communication, collaboration and knowledge sharing, we can create the future and avoid negative consequences.

Want to take the next step in exploring the future of work?

Contact the Innovate Carolina Junction team to explore future Signature Series events, speaking engagements, program creation, and how to become a member, partner or sponsor at the Junction.

Which emerging technologies, talent issues and trends do you need to understand to prepare for the professional world of tomorrow? Register to attend a Signature Series event at the Innovate Carolina Junction.

Attend the Signature Series