Using technology developed by UNC-affiliated startup Mizar Imaging, scientists can transform traditional microscopes into high-resolution instruments that let them see the inner workings of living organisms and cells in ways that weren’t previously possible. How did this startup survive an early entrepreneurial scare and a pandemic to build a company that now advances science in labs across the world?

When Paul Maddox answered the phone just before Thanksgiving in 2018, a voice on the line asked him an unexpected question: “Are you ready to get on a plane?” The caller wasn’t a family member proposing a spur-of-the-moment holiday trip. In fact, there was nothing festive about the ensuing conversation. Rather than putting Maddox in a holiday-inspired frame of mind shared by many people at that time of year—reflecting on all that they have—the phone call stirred his mind with the fear of all that he might lose.

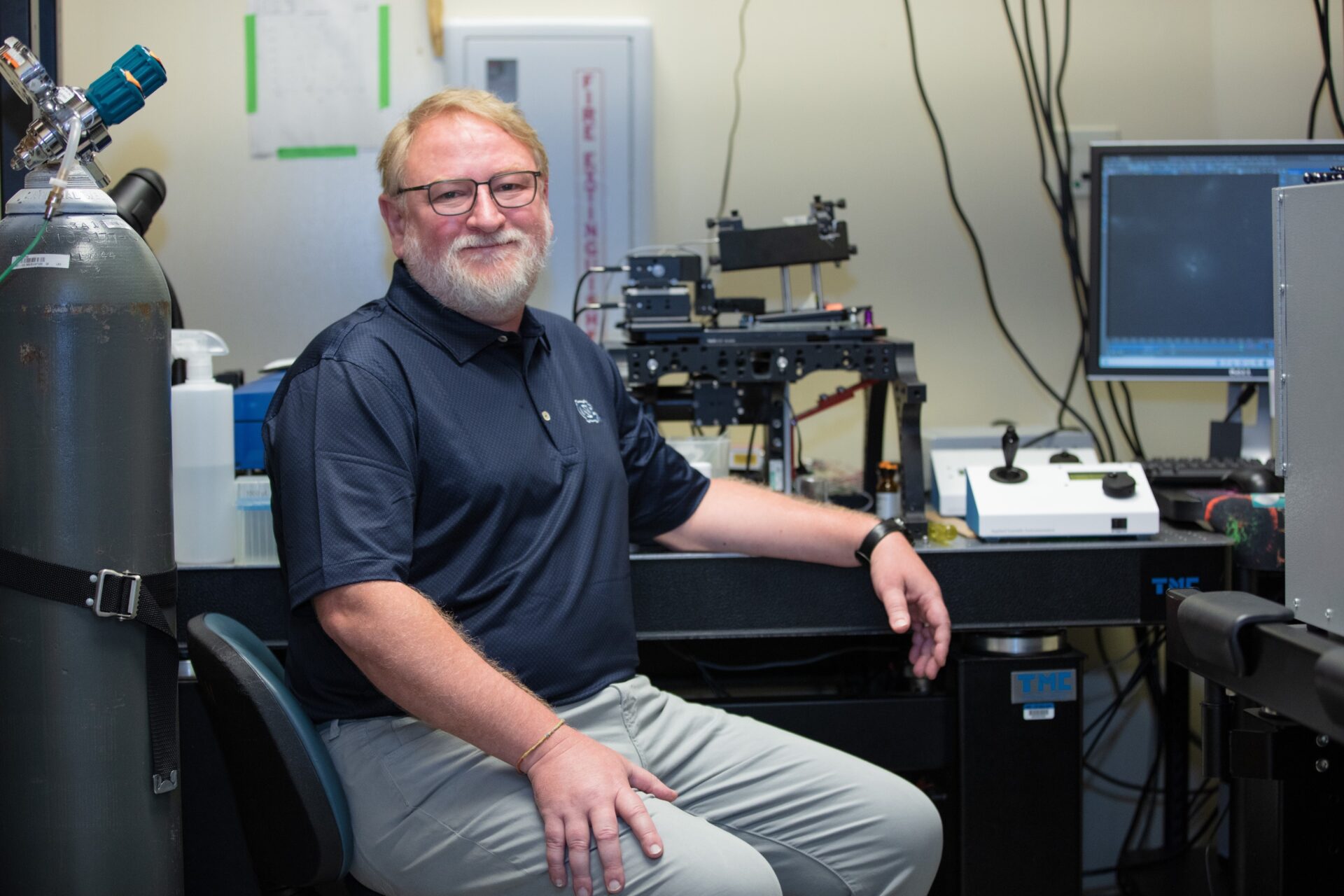

Maddox, an Associate Professor of Biology and William Burwell Harrison Scholar at UNC-Chapel Hill and also president and co-founder of startup company Mizar Imaging, listened anxiously to the caller. It was his business partner Joel Smith, the company’s CEO. Smith had bad news. Due to a supply chain snag, their company was out of money and on the verge of folding. Although the company had received plenty of orders for its light sheet microscope technology, it wouldn’t receive payment from customers—scientists working in academic labs—until after the beginning of the new year. And the company’s equipment suppliers, who had already delivered Mizar Imaging the materials it would use to fulfill the customer orders, were demanding payment now. During the call, Smith suggested that, since the company was in grave jeopardy, he and Maddox may need to book flights and hit the road—selling their equipment supply in order to pay back their primary investor.

“A lot of businesses go through a pinch,” says Maddox, who had invested personal funds into the business. “So, here we are stuck with a supply of equipment that we’d already bought, and we didn’t have the money to pay for it. And in that moment when Joel was saying we might go under, I thought to myself, ‘What have I done? Will I have the money to send my kids to college?’”

Maddox says two things saved his company. The first was his and Smith’s ability to quickly shore up additional funding: $150,000 from a new angel investor. That investment allowed them to pay suppliers until customers made payments.

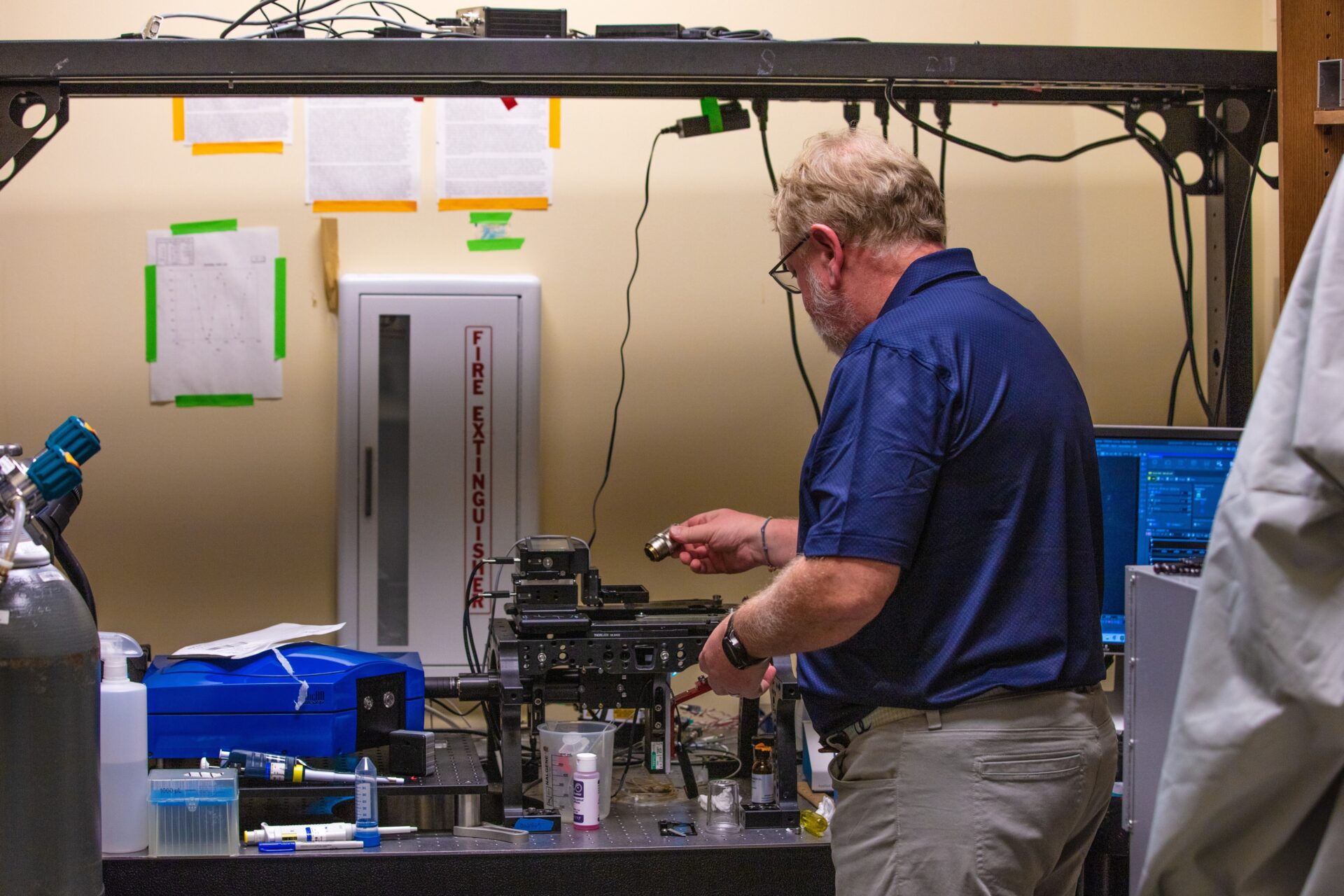

The second is what he describes as his touchstone—a grounding truth and belief in what he’d created. “For me, our touchstone is the memory of the very first time we used our imaging system,” says Maddox, who in 2015 worked with his lab assistant and later doctoral student Tanner Fadero to build an early prototype of a device that could transform a standard microscope into a high-resolution light sheet system. “The first system we built was very arts-and-crafty. We stacked it on Styrofoam coolers, and we were holding the device at an angle and moving the sample around by hand. It was tedious, but once we placed the sample in, we said to ourselves, ‘Oh my God, there it is. It works.’ That first prototype was built in the most imperfect situation and was fraught with bad design, but it made the most amazing movie I’d ever seen.”

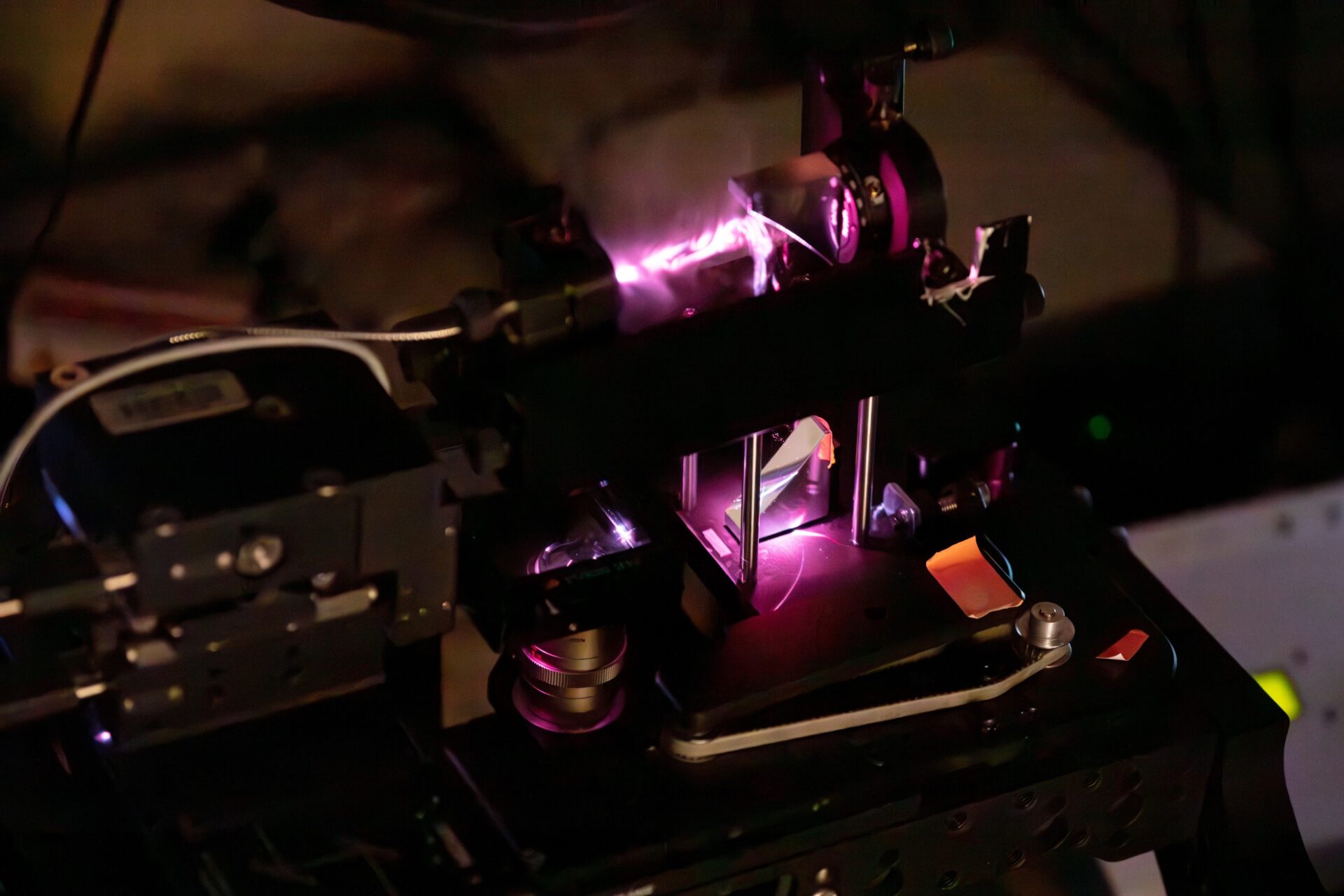

That first prototype would evolve into the company’s Tilt light sheet imaging system. Scientists can mount the system—which employs a specialized light sheet illuminator—to existing microscopes, giving them instant high-resolution light sheet imaging capabilities. This allows researchers to image living samples longer and faster than previously possible.

The Tilt technology solves a problem encountered by many scientists, including Maddox’s wife Amy Shaub Maddox, a Professor of Biology at UNC-Chapel Hill, whose need to image cytokinesis (part of the cell division process) at a high frame rate inspired the original Tilt prototype.

“With a traditional microscope, if you’re studying something that moves—for example mitochondria that move in a cell—every time you take a picture, you damage the mitochondria. They might move a couple of frames and then stop because you’ve damaged them, and now you’re unable to get information from that system,” he explains. “You could decide to take fewer frames, but you’d miss the behavior and understanding of what the mitochondria do between frames.”

By allowing scientists to use high spatial and high temporal resolution—while minimizing photobleaching and phototoxicity that damages cells—Mizar Imaging’s Tilt system helps researchers observe samples longer, collect more information, and conduct long-term imaging experiments on a variety of living organisms and single cells.

Scientists can add the Tilt system to practically any traditional microscope, bringing high-resolution light sheet capabilities to the equipment they already have.

“We designed the Mizar Tilt system around our own existing microscope at UNC, which is a common design in campus labs worldwide. That way, we can offer it as an add-on to scientists’ existing systems,” he says. “A lab might have paid $250,000 to $300,000 for an inverted microscope. For another $50,000, they can add our module to turn it into a light sheet microscope, while retaining original capabilities.”

A $50,000 upfit is a bargain compared to the alternative: buying a new light sheet microscope for nearly $1 million dollars. The Tilt also doesn’t require intensive post-processing data crunching like other light sheet systems, saving scientists time in getting useful information.

For a company named after a star (Mizar is a double star that forms part of the Big Dipper’s handle), the future is appropriately bright. For starters, Maddox says Mizar Imaging is developing a super-resolution edition of the Tilt system. He’s also launched sister startup, Mizar Therapeutics, which is a separate venture that will use imaging and machine-learning technology for the discovery of a new class of targeted cancer therapies. “The company will adapt our high-resolution, high-sensitivity live cell light sheet imaging to drug screening,” said Maddox. “This new company is not about a product—it’s a mode of discovery.”

Maddox says the angel investment received during Thanksgiving 2018 was the company’s most pivotal funding event because it kept the company afloat. Yet, he points to other critical funding sources. “In addition to the money I put into the company, our very initial funding was a $5,000 grant from KickStart Venture Services, which also included free access to legal services,” said Maddox. “The KickStart grant paid for me to give talks about the technology, hone the product, build the first five prototype units, and get into the hands of first beta test users.”

Angel investments continued to prove vital. “My key angel investor put in approximately $650,000, and that got us through pre-production and to the sales and hiring phase, allowing us to make key hires who are still with us today.”

The company—which hasn’t taken venture capital funding—has a high success rate for federal Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grants, successfully securing funding from five of seven applications. A grant-writing service offered by Innovate Carolina’s KickStart Venture Services team has helped.

“SBIR has been wonderful for us. We’ve gone through KickStart, and they helped us work with the grant writing agency InteliSpark, which teams with universities to convert IP into federal grants,” Maddox says. “It’s a pleasure working with professional grant writers because they know exactly what to do. We had a meeting with them last week, and they understood how we fit with a new call-for-proposals list. So, now we can submit three more grants. It’s a good marriage of systems—academia and industry.”

Mizar Imaging’s location has evolved with its business model. The company was founded at Maddox’s home address, a “garage-based thing” as he describes. But it quickly moved into the Marine Biological Laboratory, an international center for research and education in Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

“We had space at the Marine Biological Lab where, in the summer, hundreds of scientists from around the world come to do cell biology research, and it’s almost all driven by imaging,” said Maddox, who said the lab was an ideal location for testing ideas, gathering feedback and improving the product. He endorses the idea of scientist-entrepreneurs getting out of their own labs and working where they can easily seek input from others. “Every summer, there might be 50 critical experiments going on. We simply walked down the hall, ask scientists what they were working on, and got them to try our microscope. It was a wonderful proving ground.”

When the business model changed, the company went virtual. “We were at the lab until 2021, which was when we transitioned from a primary point-of-sale model to a distributor model,” said Maddox. “We don’t hold as much inventory now, so there’s less emphasis on the physical location.”

Like most startups, Mizar Imaging started small. Maddox and Fadero built the Tilt prototype in their campus lab. When the company was incorporated, Smith came onboard as CEO, and a few other staff members were added.

Yet, staffing up isn’t the only way the company tapped into the talent pool. It’s also developed strategic partnerships at critical moments. “We enlist partners as we move our design forward through grants,” said Maddox. “That sometimes means taking things that need specialized technical or business attention and outsourcing them to experts.”

For example, the company is partnering with an electrical engineer at the University of Georgia—an expert in using diffraction to gain resolution in light microscopes—to develop the next edition of the company’s technology: a super-resolution version of the Tilt system. Maddox and team are also working with a business development professional on the next phase of the company’s business evolution.

One of Maddox’s earliest entrepreneurial lessons came when a friend mentioned that he should consider filing a patent on the Tilt technology, something that he hadn’t initially considered. After submitting an invention disclosure through the University’s online system, Maddox met with Peter Liao, a commercialization manager in Innovate Carolina’s Office of Technology Commercialization at UNC-Chapel Hill. “When I met with Peter, I showed him my presentation, told him about the prototype and explained how everything worked,” said Maddox, who said the intellectual property process moved faster than he imagined. “Once I met with Peter, we started working to file a provisional patent that same day.”

Noting that he’s a scientist—not an entrepreneur—by training, Maddox says that he “cobbled together [his] own MBA program” to build entrepreneurial knowledge. His self-guided educational path included a mix of online videos, talking with experts, University programs like the Chancellor’s Faculty Innovation Workshop, and his own experiences. Maddox said some of the best entrepreneurial lessons that scientists can learn happen right in their labs, where skepticism is part of the natural order. “Being a scientist trains you for entrepreneurship because scientists are told ‘no’ every day,” he said. “In science, it’s rare that you’re told ‘yes,’ so we’re conditioned to explore, innovate and persevere.”