In the course of their everyday jobs, more than 8 million U.S. healthcare workers per year are exposed to hazardous drugs that could cause cancer, infertility or birth defects. UNC-affiliated startup ChemoGLO has easy-to-use products that help hospitals and other health facilities meet new national standards of practice for keeping healthcare employees and patients safe.

When pharmacists, nurses, and technicians come home at the end of the day and slide their shoes off, they’re ready to relax. But the soles of their sneakers may be harboring a hidden danger that should put them and their loved ones on edge.

The risk starts in the workplace. As nurses, pharmacists and other vital hospital workers prepare or administer chemotherapy or other potent drugs, they’re bringing hope to patients who need treatments: longer and healthier lives, remissions, and even cures. Yet their work also creates the potential for unknown and invisible dangers: the possibility that people who don’t need the treatments—themselves, work colleagues, and even family members—may be exposed to drugs that could make them sick.

“If hospital employees—whether pharmacists, technicians or nurses—are accidently exposed to and absorb chemotherapeutic drugs, it could induce pharmacologic or toxicologic effects,” said William Zamboni, PharmD, PhD, a professor and director of the UNC Advanced Translational Pharmacology and Analytical Chemistry Lab at the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy. Zamboni said that the risk of getting sick is real—from acute rashes, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, hair loss, headaches, and allergic reactions to longer-term cases of cancer, organ damage, infertility or birth defects. But he never imagined the high prevalence of exposure risk that exists until a colleague knocked on his door.

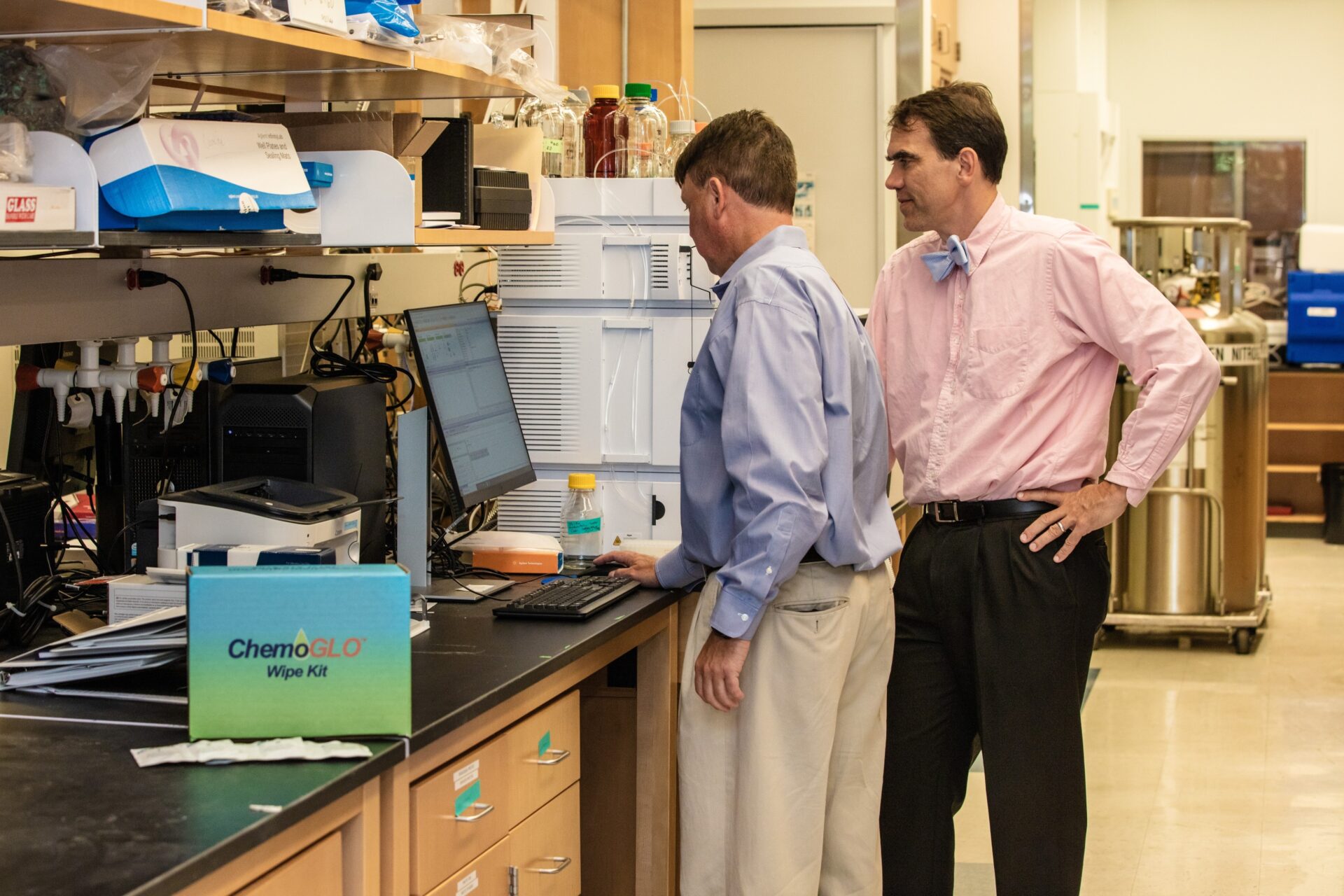

That colleague was Stephen Eckel, PharmD, MHA, associate dean for global engagement and associate professor at the pharmacy school. Eckel told Zamboni he had a hunch that such drugs could be lurking undetected in hospital workspaces and putting employees at risk.

“We started doing initial studies to measure it, and I was amazed that the drugs were everywhere,” said Zamboni, noting that 80 to 90 percent of sites tested have at least one area of detectable drug residue on surfaces. “We detected drugs in all these different areas of the hospitals where they’re making chemo—on the fume hoods, on the floor, tables—and that they’re being transported out of the IV room to other areas within the pharmacy and nursing units.” Although the drugs are initially prepared in hospital pharmacies, studies conducted by Zamboni and Eckel show that the drugs migrate to doorknobs, computer keyboards and other surfaces where they could endanger a wider group of employees.

“What shook me was the prevalence and level of exposures of hazardous drugs,” said Zamboni. “We’ve done studies showing that the shoes nurses wear at work and then wear home have chemo on the soles. This exposure is migrating—and not just out of pharmacies into nursing units. It’s migrating home.”

Alarmed by their findings, Zamboni and Eckel invented a way to reduce the threat and then launched startup company ChemoGLO to take the technology to market. “The original reason we started this company is the growing concern that when pharmacy technicians prepare chemotherapy or hazardous drugs, there is potential for them to get exposed,” said Eckel who serves as ChemoGLO’s chief pharmacy officer. “There was no method on the U.S. market that could detect that potential for exposure.”

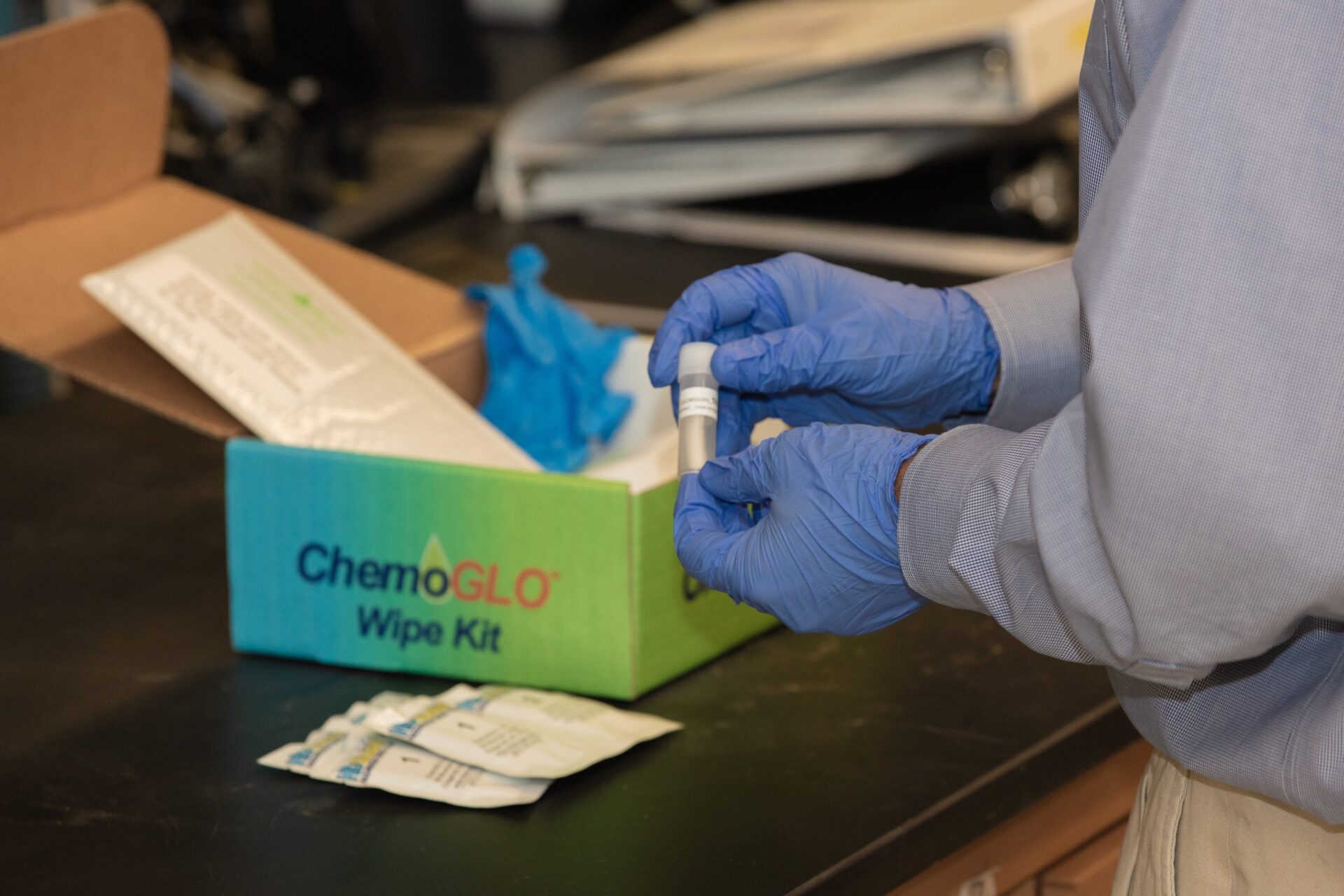

The first product that he and Zamboni, the company’s chief scientific officer, developed is the ChemoGLO Wipe Kit, which can detect and measure the presence of 24 different chemotherapeutic and hormone agents. The kits are now used globally at leading cancer centers and hospitals, making ChemoGLO the most frequently used hazardous drug monitoring company.

The kits include all materials needed for hospital staff use to test for drugs on surfaces like flow hoods, safety cabinets, infusion chairs and IV poles. Once hospital staff swab workspace surfaces, they place the samples into the kit and ship it to ChemoGLO’s lab for testing. ChemoGLO then emails results, including drug detection levels and reports that compare a hospital’s current exposure level to its prior results and those at thousands of other institutions as a comparative reference.

Beyond detecting the drugs, hospitals need to remove exposures. With so many types of difficult-to-clean drugs on various surfaces, traditional cleaning methods like alcohol and water are insufficient. So, Zamboni and Eckel invented a patented technology to eliminate contaminations. The technology became the genesis of ChemoGLO’s second product called HDClean Wipes. These wipes—which Zamboni likens in style and convenience to wet towelettes that people use to clean their hands in restaurants—are the only laboratory-tested cleaning system proven to deactivate, decontaminate and remove a wide range of drugs from surfaces. The cleaning wipes are popular and used in hospitals, nursing units, compounding pharmacies, and home health care settings.

New standards of practice make a detection and cleaning system like ChemoGLO increasingly important. November 1, 2023 is the deadline for hospitals and other healthcare institutions to meet updated safety standards established by the U.S. Pharmacopeia Convention (USP). The standards, called USP General Chapter 800 (USP 800), are designed to minimize exposure risk for healthcare personnel and patients to drugs classified as hazardous by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

“We anticipated the USP standards coming down the pipeline and designed our products to meet those recommendations before they were launched,” said Zamboni. “Both the monitoring and cleaning products are USP 800 compliant.”

With more than 30,000 ChemoGLO monitoring wipe studies performed, the company has compiled an extensive database of insights it uses to help organizations like USP and individual hospitals understand how to best keep healthcare workers safe.

“Over the years, we’ve developed a database of different institutions—whether you’re a large institution, a big cancer center, a small cancer center, or even an office—that tells us what the hotspots for detecting chemotherapy are,” said Zamboni. “How many drugs should you test for? How often should you test? With the database, we can guide policies for different groups and determine the best way: where, when and what to measure.”

Zamboni and Eckel say that being a university spinout solely focused on hazardous drug monitoring and cleaning—in contrast to the many lines of business at larger corporations—sets ChemoGLO apart.

“We bring an academic approach to the company by studying, analyzing and putting our work under peer review, using science to advance the field,” said Eckel. By doing so, the company can help hospitals interpret testing results and develop management plans in ways that other companies can’t. “We’ve always viewed ourselves as educational resources,” said Eckel. “As this regulation comes out in November, our intent is to continue collaborating with customers to keep employees safe.”

When Zamboni and Eckel launched ChemoGLO, they partnered with a large medical device company, which became the startup’s first customer. The partnership molded ChemoGLO’s funding model.

Eckel notes that, with the large company partner, “we actually started out with a market right at the beginning, which meant we didn’t have to take external funding.” But ChemoGLO intentionally diversified its customer base and funding streams. “We made sure we weren’t 100 percent dependent upon that first large customer, because if they decided not to use us, then we would’ve been in trouble,” he said. “We moved into a market where most of our sales come from individual hospitals.”

The combination of a diversified customer base and a streamlined business allowed ChemoGLO to build its business and technology portfolio on its revenue stream rather than loans, grants or investors. “We’ve been approached by groups that wanted to invest in us, but we haven’t had to take the funding because we reinvested our profits,” said Zamboni. “We’ve stayed lean and mean and reinvested our profits into our efforts to scale up and develop our cleaning products.”

ChemoGLO originated on the University’s campus. “We did the analysis for our first company partner in my UNC lab because it started as a research project,” Zamboni said. “And all the R&D for the HDClean towelette product was done in my lab, with Stephen’s intimate involvement in developing the product.”

As customer demand skyrocketed, so did the need for off-campus spaces. “Demand was doubling every year, and the workload and number of samples became too great for my UNC lab,” said Zamboni. “When it became too big to offer as a service from campus, it was time to spin out into a separate entity.”

ChemoGLO now has lab space in Durham. The towelette wipes are made exclusively in the United States, and ChemoGLO also has a warehouse in Baltimore for centralized product distribution.

ChemoGLO began with a nucleus of five employees, which includes Zamboni, Eckel, a chief executive officer, chief business officer and head of sales. “We turned to people and colleagues whom we knew could help us right away—even part time—as we grew,” said Zamboni.

Between additional lab, sales and warehouse staff, the company has grown to more than 35 employees. Along the way, increasing ChemoGLO’s sales capacity required creative, resourceful thinking.

“Sales are an important component of any business,” Zamboni said. “At ChemoGLO, we relied on our distributor relationships and strategic partnerships to increase revenue and reach new markets.”

Part of the entrepreneurial learning process involved working with mentors and programs at the University—particularly during the initial intensive ramp-up period. “We didn’t understand how hard it would be,” he said. “Early on, when we were bootstrapping the company, there were a lot of late nights, and we had a lot of people give us good advice.”

Resources included KickStart Venture Services, which provided early coaching. Zamboni and Eckel also worked with the Office of Technology Commercialization (OTC) to protect ChemoGLO’s intellectual property, secure a patent on its technology, and establish a licensing agreement between the University and company. Both KickStart and OTC are part of Innovate Carolina, UNC-Chapel Hill’s central team for innovation, entrepreneurship and economic development.

Protecting intellectual property was a learning process, but one that Eckel said the team was able to streamline. “The most valuable resource was being at a university that supports faculty startups, because I’ve talked to faculty at other places who don’t have the same structure and encouragement that we do,” said Eckel. “UNC has resources and advice that have been helpful for us, like templated licensing agreements that we could follow. All those things made the learning process much easier.”

Both Eckel and Zamboni learned from the mentorship of Dhiren Thakker, PhD, professor emeritus and former distinguished professor and interim dean of the pharmacy school.

“I was involved in research—not in starting companies—and was somewhat naive about the intellectual property process,” said Zamboni. “Dhiren Thakker told us, ‘The research you’re doing could be a viable company with patent protection.’ Dhiren was a big influence in helping us understand that this could be a commercial entity and what steps to take. He was a tremendous mentor and gave us the vision for what this could be.”