A big part of this for us has been stubbornness – to not quit when our initial grant application got rejected again and again. Eventually, we succeeded with that first pilot funded study from the NSF, and about ten other grants followed. But the willingness to keep going even though your initial attempts fail has been our key to success.

I think most faculty members and grad students are more entrepreneurial than they give themselves credit for. They work tirelessly to push the ball forward for their niche in the scientific community. In a way, that’s a big part of forming and growing a startup company. You identify a pain or problem in the market, and work tirelessly to figure out a way of solving it. And there’s no playbook for it, you’ve got to figure it out as you go. Which is the same as any research project in a lab. And just like any professor running a lab – your money is always running out and it’s a race against the financial hourglass to land your next customer, paper or grant, or to determine what you’re working on is doomed to fail and you pivot before the money runs out.

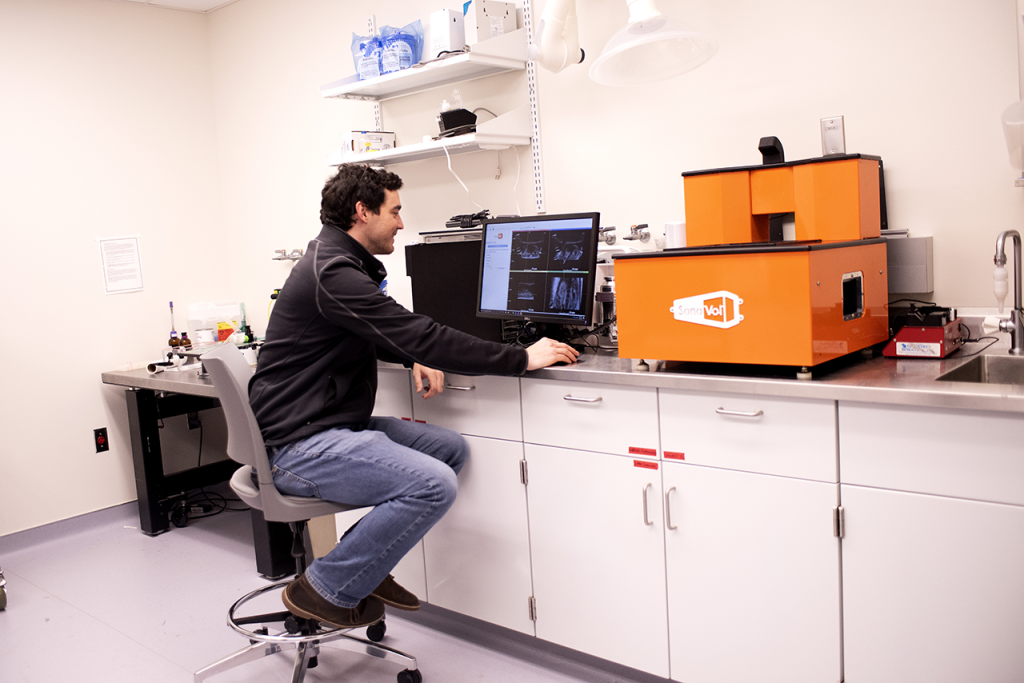

| UNC-CH

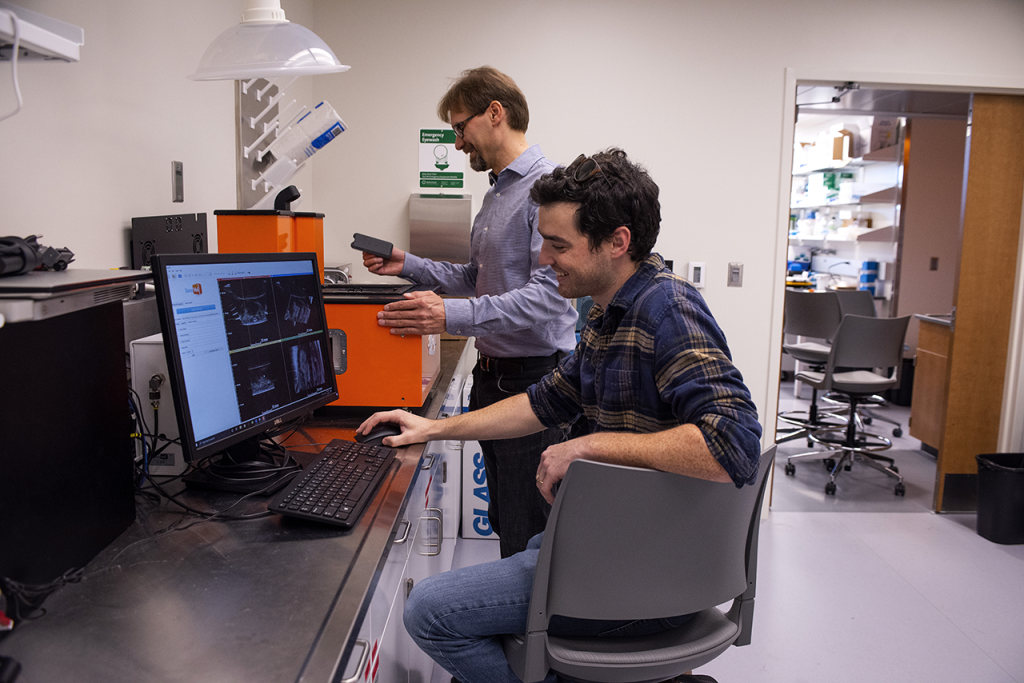

| UNC-CH